Move on up?

The Navy, the North, and the new Russian threat

This royal throne of kings, this sceptred isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in a silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands,

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England.

– John of Gaunt, Richard II, Act 2, Scene 1.

It is a tragedy of geopolitical theory that William Shakespeare goes unrecognised among the great canon of strategic thinkers. Few would think to place him with the likes of Alfred Thayer Mahan, Sir Halford Mackinder, Sir Julian Corbett or Adm. Sergey Gorshkov – men of sensible ideas and scholarly research.

Yet, his majestic prose communicates the inherent advantages of British geography in a way no other strategist has captured before or since. Sir Winston Churchill, himself no stranger to high oratory, rightly claimed that John of Gaunt’s dying words ‘still thrill like the blast of a trumpet…not only because they are beautiful, but because they are true’.

Perhaps less beautiful, but certainly no less true, is the 2024 Defence Committee report on the United Kingdom’s (UK) warfighting readiness. The report’s remit covered three areas of readiness: operational, warfighting and strategic. It concluded that on all three counts, Britain fails miserably.

Current deployments are unsustainable – ‘in excess of what the force structure was designed for’ – infrastructure and munitions stockpiles suffer from a chronic lack of underinvestment and strategic readiness is lambasted as ‘more of a concept under debate…than an agreed policy’.

Such findings apply too in the North Atlantic, where the UK demonstrably lacks strategic advantage in its near ‘silver sea’. Too often, suggestions on how to fight and win wars rely heavily on adjectives – ‘innovative’, ‘lean’ and ‘agile’ solutions. Reality, however, deals in nouns: the physical cranes, ship lifts, dry docks and missile systems which will deliver either deterrence or victory.

Accordingly, achieving success in the North Atlantic requires a physical reorientation of the Royal Navy’s fleet to face the Russian threat, and the recovery of meaningful shipbuilding and repair capacity to the defence industrial base.

Move on up

The Royal Navy has a long history of repositioning home forces to combat overseas opponents. Wars against the Dutch required concentration in the South East (Chatham, Portsmouth and Sheerness), while wars against the French saw forces distributed to Plymouth (to blockade Brest) and Portsmouth (to hold the Channel). In the 21st century, there is no military posture more necessary, and indeed more popular, than that which is Russian-facing.

Seven in ten British citizens view Russia as a threat, likening Vladimir Putin, President of Russia, to Hitler and holding Russian aggression in contempt. If there is a universal conviction in the UK today, it is that ‘Britain is a European military power and can help deal with Europe’s main military problem: Russia’.

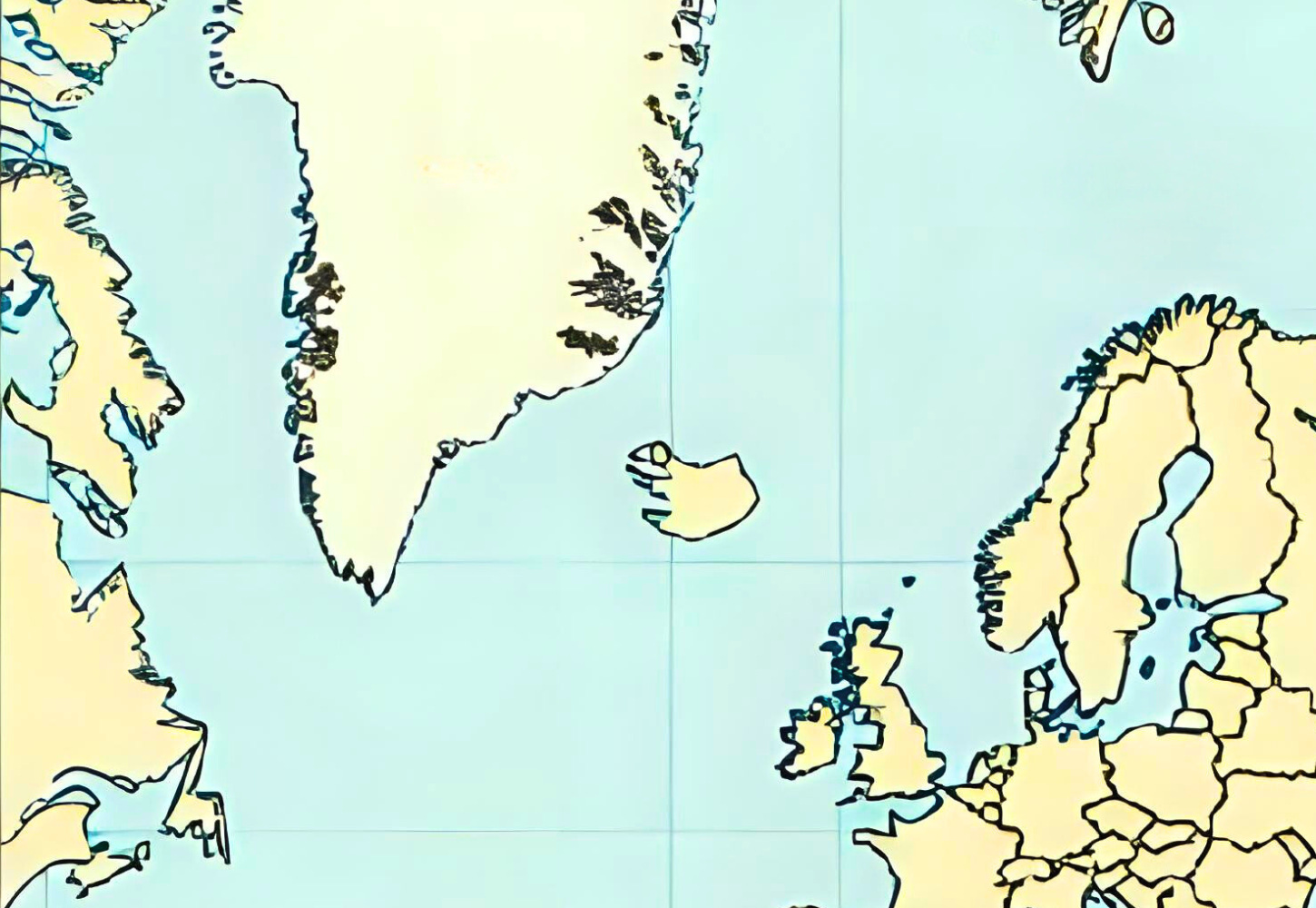

Were the UK in a position wherein it was required to defend the North Atlantic alone, it should learn ‘how to acquire and wield [hard] power’, repositioning its naval forces to deter the Russian threat. Given Russia’s two entry points into the North Atlantic are the Øresund Strait (the Sound) and the Greenland-Iceland-UK (GIUK) gap, the Royal Navy should prioritise basing the next generation of frigates in ports with the most direct access to these theatres, saving considerable time in transit, as well as placing the fleet on best footing for an increasing tempo of Russian sallies.

The current structure of Fleet Ready Escort (FRE) duties compels platforms based in Plymouth to transit the length of Britain to meet any potential adversary, introducing unnecessary friction into an already gritty operation. Re-appropriating Rosyth is one obvious choice, but other options include establishing Type 31 frigates on the east coast of England, namely re-capitalising latent shoreside facilities in Tyneside.

Basing Type 31s on a rotational crew basis in the Tyneside region holds considerable promise, both at a national strategic and local level. In 1996, British defence accounted for some 400,000 jobs in the country, yet post-Cold War reductions and austerity have resulted in contemporary figures of under 165,000, concentrated in the South West, South East and the Scottish Central Belt.

By and large, the North East is abandoned, receiving £1 for every £38 spent in the South by the Ministry of Defence (MOD). If there is a way to retain the loyalty of the British Armed Forces’ prime recruiting ground, it is with a strategic re-posturing of the fleet, which offers stable, highly paid and technical employment in service of the country and with prestige in the community.

The royal ‘arsenal of democracy’

Any repositioning of the Royal Navy’s surface capabilities also requires a renewal of the defence industrial base to support an ever-increasing operational tempo. For this, the UK should look to the United States (US). Washington is increasingly leveraging the industry of partners to conduct in-theatre ship overhauls and repairs, saving its own domestic facilities for much-needed construction. Five such hubs have already been launched in a pilot programme across the Indo-Pacific, with the intention to roll out similar agreements across Europe.

Even the staunchly protectionist Trump administration approves of this Biden-era measure, endorsing the use of foreign yards for ‘routine maintenance and repair’ and manufacturing select components. Large American warships will now undergo extensive refits in foreign yards, with the US securing local supply chains and the host nations a reliable stream of industrial work.

There is little reason why Britain should not actively encourage such a hub in the North East, investing some of the hundreds of billions saved during the ‘peace dividend’ into the recapitalisation of British dockyards. Half of A&P Tyne’s dry docks are currently unused, while the dry docks and slipways of Hawthorn Leslie and Swan Hunter lie derelict.

Pallion, in Sunderland, was the largest covered shipyard in the world when it closed in 1988. Plans have been submitted to turn it into a ‘water film studio’, with no capacity for dual use in the event of conflict. However, the success of Cammell Laird in Birkenhead shows that with determined will, and a regular drumbeat of government orders, the return of skilled industry is an achievable goal.

A similar miracle could well occur on the Tyne, encouraged by a renewed Royal Navy presence and the potential for American repair tenders. This island fortress may well have been ‘built by Nature’, but it requires determined action to maintain it.

Joe Reilly is a Sub-Lieutenant in the Royal Navy, currently serving as an Initial Warfare Officer onboard HMS Cattistock. He has written extensively on matters of maritime and national strategy, with his work winning various awards in the UK, Australia, and the US.

To stay up to date with The Broadside, please subscribe or pledge your support!

What do you think about this article? Why not leave a comment below?

Whilst I think you make an excellent point about divesting away from being centred on the South coast (Faslane notwithstanding), I don't think the Royal Navy can afford to wait for Type 31 to enter service. This has to be done as soon as possible, for no other reason than to start the regeneration of these long-neglected facilities. Vessels based on the East coast would be in a good position to intercept Russian ships leaving the Baltics, deploying via the Channel to areas such as the Mediterranean.

I think the bigger headache is going to be a combination of reintegrating the Royal Navy into areas long since abandoned, and convincing families of those sent 'Up North' to relocate in sufficient numbers to make it a going concern.

https://open.substack.com/pub/thebluearmchair/p/slouching-towards-bethlehem?r=5kmhkr&utm_medium=ios