What if one of the CRINK nations cut data cables to the UK?

Silver award winner for the First Sea Lord’s Essay Competition 2025

This piece was written in April 2025 for the First Sea Lord’s Essay Competition, and was awarded Silver at the International Sea Power Conference 2025.

The United Kingdom (UK) is a strategic linchpin in global internet infrastructure, with a dense network of submarine communications cables landing on its shores – notably in Cornwall, Kent and Suffolk. These cables carry up to 95% of the world’s intercontinental data traffic, linking North America, Europe and beyond. As such, they are not only technical assets, but geopolitical chokepoints whose disruption could cripple financial transactions, military Command and Control (C2), and diplomatic communications. From the First World War, when Britain cut Germany’s global cable network on day one, to the present, control over undersea communications remains a strategic imperative.

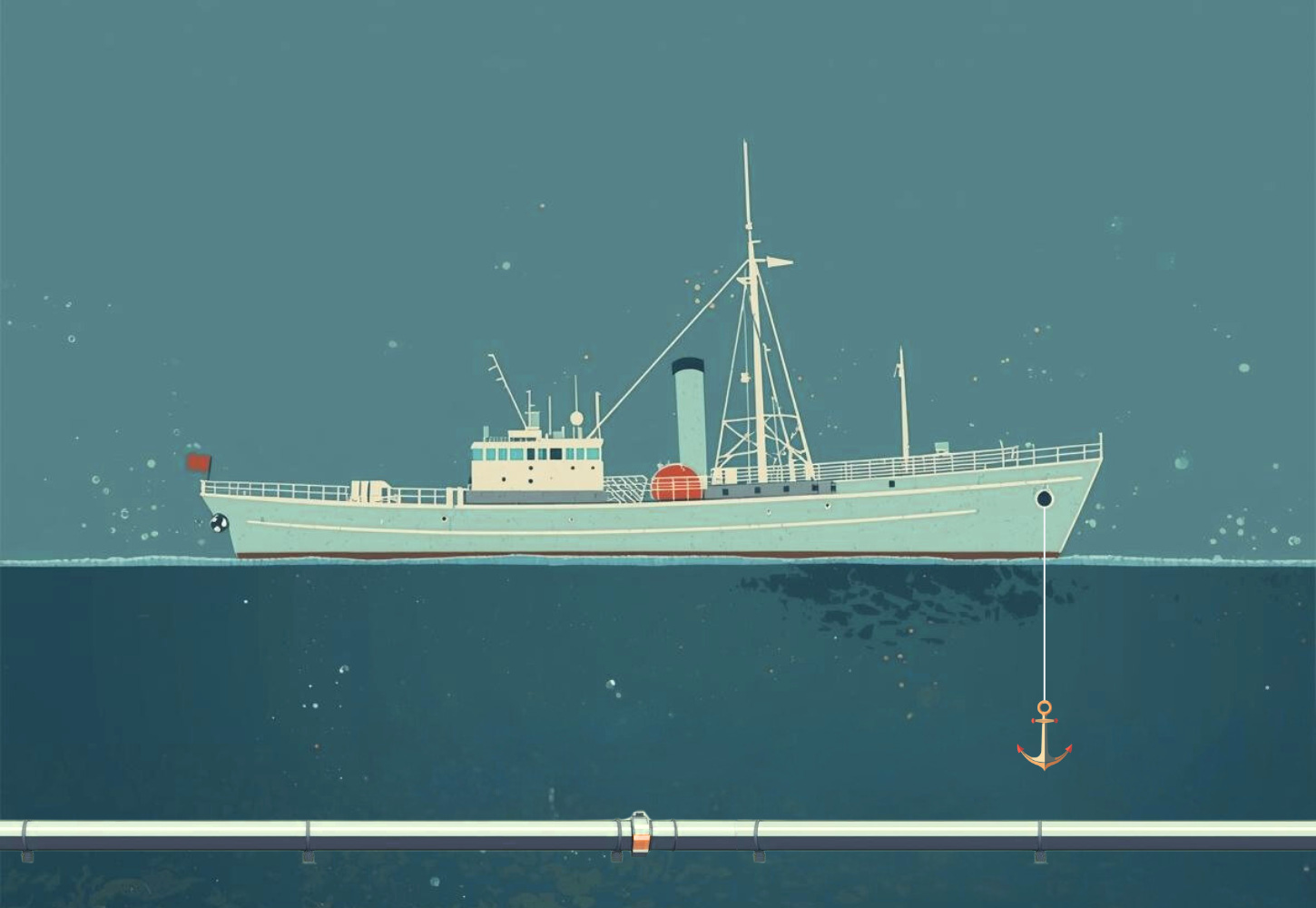

Today, the threat landscape has evolved. Recent discoveries of Russian acoustic sensors near the UK’s Trident submarine routes and Chinese experimentation with autonomous cable-interdiction devices illustrate a growing convergence of capability and intent. Historical precedents of cable tapping, such as Operation IVY BELLS, are now joined by modern realities: plausible deniability, sub-threshold operations, and the use of shadow fleets and hybrid vessels to conduct deniable actions.

The presence of highly specialised platforms, such as the Yantar, a Russian ‘research vessel’, and the Belgorod, a Russian-flagged tanker, supported by an ecosystem of undersea platforms including Losharik, Paltus, Klavesin and Shelf, underscores the scale of the challenge. These platforms allow for precision seabed operations, cable mapping and covert sabotage, all under deep-sea concealment. The sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines also highlights that such undersea attacks are not limited to data cables alone; critical oil and gas infrastructure is equally vulnerable.

Importantly, the strategic logic behind cable attacks is not necessarily military victory, but political disruption. Disinformation campaigns, narrative engineering and attempts to shake confidence in North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) cohesion are the true objectives. As such, free and open nations’ responses should not only be kinetic or technical, but psychological and legal as well.

Retaliating in kind, for example by cutting cables to ‘CRINK’ states – the People’s Republic of China (PRC), Russia, Iran and North Korea – would undermine Britain’s norms-based posture. Instead, its goal should be to deny adversaries the effects they seek: widespread panic, loss of services or political destabilisation. Attacks should be rendered both ineffective in outcome and prohibitively expensive in terms of operational effort and political risk.

The Royal Navy is already a capable force in this domain, with assets such as the Type 23 frigates, Merlin and Wildcat Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) helicopters, and the recently commissioned Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) Proteus offering tools for undersea surveillance and response. Complementary assets include Mine Countermeasure Vessels (MCVs), the dedicated RFA Stirling Castle and P-8 Poseidon MRA1 Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA).

This fleet offers layered coverage from surface, subsurface and airborne platforms. However, it remains numerically limited. Legacy procurement cycles are both expensive and slow, and readiness rates have been a consistent concern. As many within industry and defence circles suggest, what the UK needs is not only high-end capabilities, but affordable mass; to adapt, Britain should adopt a five-pronged strategy.

First, the Royal Navy should deploy a persistent network of seabed sensors, both fixed and mobile. Passive acoustic arrays; naval drones, such as the Slocum gliders trialled under Project HECLA; and technologies inspired by programmes such as the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Persistent Aquatic Living Sensors (PALS) should be integrated into both British and NATO undersea monitoring efforts.

Second, patrol tempo should increase in known cable corridors. While platform count is constrained, improved readiness and the development of multirole support vessels – similar to the Nordic model – can stretch existing capabilities. These vessels are not only operationally flexible, but also more efficient in capital utilisation, offering cost-effective solutions adaptable to a wide array of missions.

Third, the Ministry of Defence (MOD) should accelerate investment in uncrewed and autonomous maritime systems. This includes Uncrewed Surface Vehicles (USVs) and Uncrewed Underwater Vehicles (UUVs), from small sensor-bearing vehicles to Extra Large ‘XL’ models with persistent endurance. Artificial Intelligence (AI)-enabled maritime domain awareness systems – whose development can be coordinated by the Defence Artificial Intelligence Centre (DAIC) in collaboration with stakeholders such as the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) and Defence Equipment and Support (DE&S) – should be prioritised.

Additionally, supporting initiatives such as the NATO Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic (DIANA) and the NATO Innovation Fund (NIF) can provide a strategic boost to early-stage capabilities. Overhead support from High Altitude Platform Stations (HAPS) and Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) satellites can further relieve warships from stationary monitoring roles, allowing them to concentrate on deterrence and response.

Fourth, international collaboration is crucial. Expanding the scope of the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) or creating a new multilateral task force for undersea infrastructure protection would allow allied burden-sharing. Wargames and naval exercises should include cable disruption scenarios, while private sector capital and expertise can be leveraged via public-private partnerships, especially in emerging dual-use technologies. Doctrinal evolution, particularly in sub-threshold escalation management, should accompany these operational reforms.

Finally, engagement with telecom providers should become institutionalised. The majority of the cables are privately owned; thus, shared threat intelligence protocols, resilience audits and incident response plans are essential. Investments should also be made into rapid repair platforms and technologies capable of flagging and investigating cable disturbances in real time. Additionally, technical innovations in cable design could support integrated sensing capabilities to raise early alarms of tampering.

Ultimately, Britain must recognise that undersea cables are no longer just critical infrastructure – they are contested strategic terrain. The response to threats in this domain must be equally multidimensional: blending defence readiness, allied coordination, technological innovation and legal-psychological resilience. Only then can the UK ensure that future sub-threshold threats, whether from Russia’s shadow fleet or the PRC’s autonomous saboteurs, are denied the very impact they seek to achieve.

Francesco Canossi is an aerospace and defence professional, with a background in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM). He is also a Fellow of the Council on Geostrategy’s Maritime Leaders’ Programme.

To stay up to date with The Broadside, please subscribe or pledge your support!

What do you think about this article? Why not leave a comment below?