Navigating the funding storm

The coming sea power crisis

The Royal Navy is currently in the middle of a ‘golden decade’ of shipbuilding aimed at recapitalising the entire fleet within the next ten years. With 19 vessels on contract or under construction, and more planned, this represents a substantial boost to the United Kingdom’s (UK) naval capability. There is a longer-term risk ahead: that by the 2060s, the financial challenge of replacing these new vessels could potentially lead to the worst budgetary fights the Royal Navy will have experienced in over a century.

The Royal Navy did not intend for this ‘golden decade’ to happen. It is an unintended legacy of decades of defence reviews and planning rounds, where deferrals and delays have been approved to make the short-term books balance, even if it means long-term pain. The result is that Britain has a much smaller, increasingly elderly and materially fragile fleet while waiting for the new fleet to arrive.

The whole future fleet, as well as the current Queen Elizabeth Class, will reach their out-of-service dates between 2058 and 2070. This means that to replace them, the Royal Navy will need to secure sufficient funding to regenerate its entire fleet, run on existing ships and plan for the mass introduction of new ship and submarine types within a decade of each other. This will be the single biggest peacetime building requirement ever seen for the Royal Navy, and is likely to be unaffordable and undeliverable as it stands.

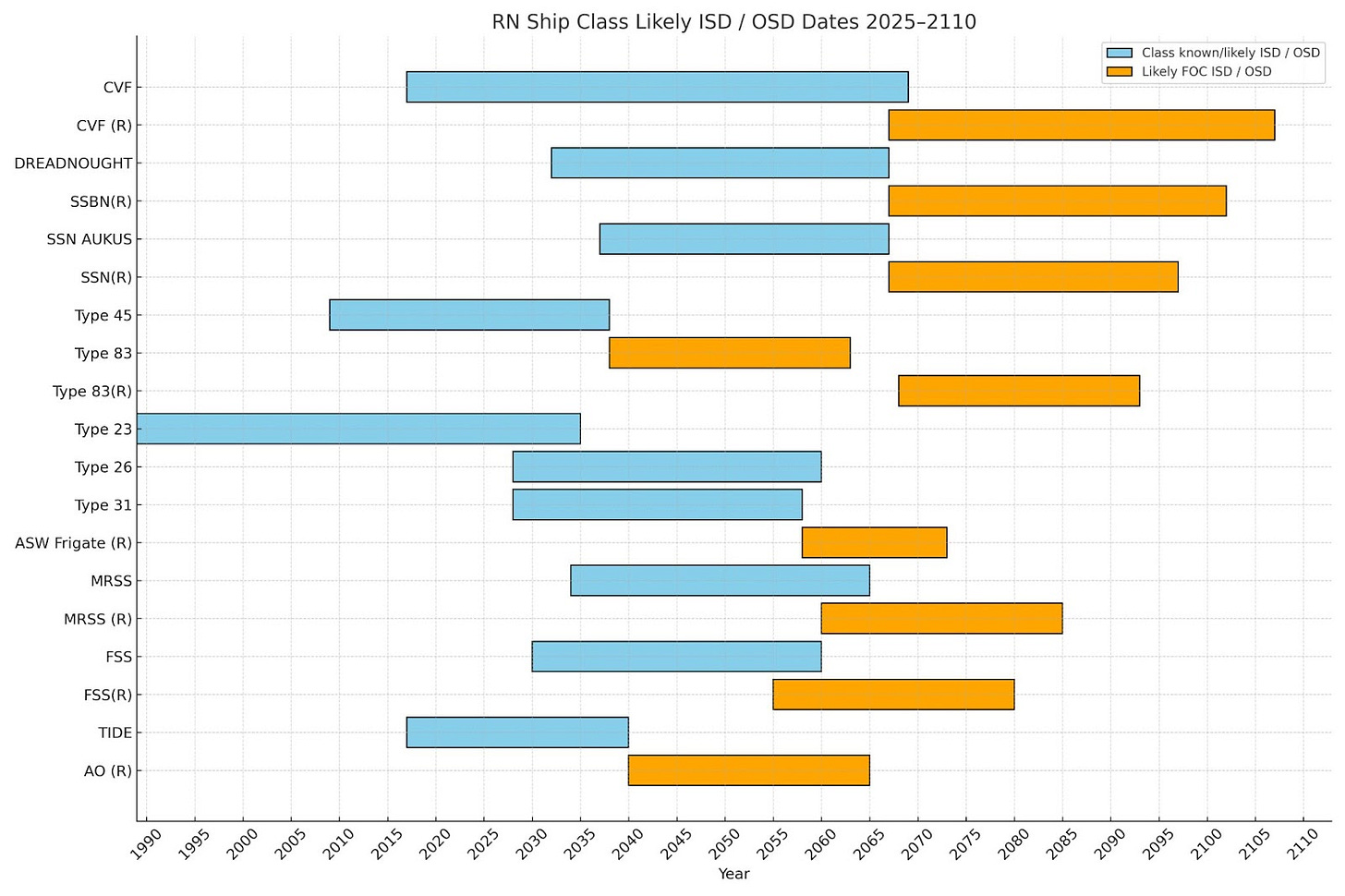

Graph showing known/projected in-service dates (ISDs)/out-of-service dates (OSDs) for current, future and likely capability replacement. All future dates are indicative, based on an assumption of 25-30 year hull life and likely ISD/OSD for the first of each class.

The biggest challenge will be that the nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN), carrier and surface escort force will all need to be replaced in this time. By 2065, the Dreadnought class will all be over 30 years old, and rapidly approaching the end of their hull life (projected to be 35-40 years). To be certain of continuing continuous at-sea deterrent (CASD) operations – and marking the 100th anniversary of Operation RELENTLESS in 2069 – a new class of SSBN, and a replacement for the Trident missile and warhead system, will need to be entering service by the late 2060s. At the same time, the Queen Elizabeth class will be paid off by 2069, meaning replacement aircraft carriers (and associated air assets) will also be required in the same time frame. Meanwhile, the Type 26, 31 and 83 escorts will all need replacing between the late 2050s and early 2070s, either by like-for-like platforms or entirely new technologies.

This is not a future problem though. The implications of future decisions will be felt within the next few years. Historically, major Royal Navy replacement concept work usually starts about 20 years ahead of time; for example, Carrier Vessel Future (CVF) design work for the Queen Elizabeth class began about 1993. The Royal Navy will need to begin concept work and forward financial planning for new carriers within the next 15 years. The Dreadnought class design work dates to 2011, and first steel was cut in 2016, with projected entry to service in the ‘early 2030s’. To replace her in 2068 will mean work starting in the mid-2040s, when the SSN-AUKUS programme is ramping up.

Both SSBN and CVF replacements will need political approval and secure long lead funding within the next 20 years to be certain of getting replacements in service. The last time the Royal Navy tried to procure a replacement carrier and introduce SSBNs at the same time was in the 1960s. It proved unaffordable, with CVA-01 being cancelled and the carrier force withdrawn from service.

Some will counter that the future fleet will not be like the current force, and that it will be focused on autonomous/uncrewed vessels, drones, etc. Even if this is the case – and the argument focuses on capability, not platform – this does not remove the need to fund a replacement of some form, be it land, sea or space based – and it will be expensive. For example, the Type 83/Future Air Dominance system and its replacement may rely on both crewed and optionally crewed vessels.

The Royal Navy needs to be ready to fight and win the biggest Whitehall funding battle in centuries. Over the next 20 years, it will need staff officers capable of making a compelling case, not just for sea power as a concept, but for the funding of the total replacement of the entire fleet in some form, and associated investment in infrastructure, training and people to deliver a radically new fleet to the nation within barely a decade. This will require political support and a willingness to find an inordinately large share of funding to deliver this project at a time when the Royal Air Force (RAF) and British Army will also have expensive equipment requirements to be funded.

This may feel academic and downbeat, given the exciting new construction which lies ahead for the UK, for a problem which lies decades in the future. But the people who will need to make the early decisions on how and whether to replace the carrier fleet and CASD are already in the Royal Navy – they are junior officers and ratings today, but within 20 years they will be commanders and captains charged with setting the policy and budgetary decisions which will shape the size, structure and role of the Royal Navy for decades to come. The future First Sea Lord of the 2060s, who will be responsible for introducing these platforms and capabilities, is probably already undergoing training at Britannia Royal Naval College (BRNC) Dartmouth or Commando Training Centre Royal Marines (CTCRM) Lympstone.

The corporate memory of the Royal Navy stretches back about 40 years, and looks forward about 40 years. Taking a strategic view, 2060 may feel a long way off, but that is only 35 years from now – the equivalent of thinking about the Royal Navy of 2025 in 1990.

The Royal Navy needs to be clear in its vision, not just for the Navy of 2035, but also for the Navy of 2065. It needs officers and ratings to understand the changes ahead, and to see it as a genuinely ‘whole career’ journey for them to deliver two radically different naval forces within one career. Senior officers are arguably shaped by the formative experience of the service they joined. To be certain the next generation of officers can make the case in Whitehall – and beyond – for the future regeneration of the Royal Navy, there is a need to set a clear vision now for the Royal Navy of 2065 and beyond, giving a guiding light by which today’s sub-lieutenants can steer a course to the day when they are admirals setting the vision for the Royal Navy of the 22nd century; for when the current crop of trainees leave in 40 years; and when their successors will be serving into the 2100s.

A whole career vision of force development is needed: plans, capability development and financial planning should not be the preserve of Navy Command Headquarters (NCHQ) and Main Building, but openly discussed, debated and shared among the force to help build shared ownership of the future vision of sea power. The Royal Navy needs to do everything possible to train these young sailors now, not just in the art of sea power, but also in ensuring the wider workforce sees their mission as generational delivery of capability for a nation, not short-term planning, and in turn, how to make a compelling case for investment in sea power and the Royal Navy – in Whitehall and beyond – to secure the necessary funding to deliver it on behalf of Britain.

Lt. Cdr. James Waller RNR has served as a volunteer reservist in the Royal Navy since 1998, including in Iraq, Afghanistan and the wider Middle East. In his main career, he has extensive cross-Whitehall experience working on defence and wider security issues.

The views expressed in this article are personal and do not necessarily reflect those of His Majesty’s (HM) Government.

To stay up to date with The Broadside, please subscribe or pledge your support!

What do you think about this article? Why not leave a comment below?